To summarize, Zucman’s “stunning graph” in the NYT is a result of two acts of data manipulation.

1. He suppresses the true effective tax rate on the rich over time by misallocating corporate tax incidence to them.

2. He simultaneously inflates the rate for the poor by excluding EITC

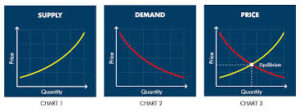

Economic organization is a wicked problem. Your intuition might be that the best approach would be for a department of experts to determine what goods and services get produced and how they are distributed. This is known as central planning, and it has not worked well in reality. The Soviet Union fell in part because its centrally planned economy could not keep up with the West.

Some advocates of central planning have claimed that computers could provide the solution. In a 2017 Financial Times article headlined “The Big Data revolution can revive the planned economy,” columnist John Thornhill cited entrepreneur Jack Ma, among others, claiming that eventually a planned economy will be possible. Those with this viewpoint see central planning as an information-processing problem, and computers are now capable of handling much more information than are individual human beings. Might they have a point?

F.A. Hayek made a compelling counterargument. In a famous paper called “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” first published in 1945, Hayek argued that some information is tacit, meaning that it will never be articulated in a form that can be input to a computer. He also argued that some information is dispersed, meaning that it is known only in small part to any one person. Given the decentralized character of information, a market system generates prices, which in turn generate the knowledge necessary to efficiently organize an economy.

A central computer is not going to know how you as an individual would trade off between two goods. You may not be able to articulate your preferences yourself, until you are confronted with a choice at market prices. The computer is not going to know how consumers will respond to a new product or service, and it is not going to know how a new invention might change production patterns. The trial-and-error process of markets, using prices, profits, and losses, addresses these challenges.

Economists have a saying that “all costs are opportunity costs.” That is, the cost of any good is the cost of what you have to forgo in order to obtain it. In other words, cost is not inherent in the nature of the good itself or how it is produced. It is impossible to know the cost of a good until it is traded in the market. If central planners do away with the market, then they will not have the information needed to calculate costs and make good decisions. Forced to use guesswork, planners will inevitably misallocate resources.

In a market system, bad decisions result in losses for firms, forcing them to adapt. Without the signals provided by prices, profits, and losses, a central planner’s computer will not even be aware of the mistakes that it makes.

A coddled coterie of malcontents—initially centered at elite universities—spent April taking over buildings, shutting down classes, and hurling antisemitic slurs in the name of “pro-Palestinian” activism. Politically, the obvious response was always simple. Neither the masked mob, nor their cause, is remotely popular.

…..

That’s the biggest threat brought on by Mr. Biden’s failure to defend his own policies forcefully. The president desperately wants the youth vote, but his tiptoeing is costing him the support of millions of Americans who are already disgusted by the wokeism of higher education, soaring tuition bills, and Mr. Biden’s student-loan gifts. Many have children or grandchildren at college who are being robbed of classes, finals and, potentially, graduation ceremonies.

Mr. Biden’s repeated failures to take a stand against his left’s worst instincts are directly related to his current abysmal approval ratings. It isn’t quite too late for him to step up as a leader, but it soon may be.

Richard Rahn asks: “What would Eisenhower have done about Columbia University?” Here’s his conclusion:

In the past, employers would pay a premium for the graduates of the Ivy League, Stanford, the University of Chicago, and other top schools, with the assumption that they were better educated and more open to new ideas. That exaggeration is now being exposed. The market will work — less famous schools (including non-American ones) will see and exploit the opportunity to create world-class educational programs and thus attract the best students. May the legacy schools rest in peace.

George Will looks at the 2024 American electorate. A slice:

Because so many Democratic voters are in California (13.7 percent of the party’s national popular vote total in 2020) and a few other noncompetitive states (e.g., Illinois, New York), the party probably must win the national popular vote by more than 3 percentage points to win 270 electoral votes. Oddities abound. Gerald Ford came closer to defeating Jimmy Carter in the 1976 popular vote than Mitt Romney came to defeating Obama in 2012. Clinton, losing to Trump in 2016, won the popular vote by a larger margin (2.1 points) than John F. Kennedy did defeating Richard M. Nixon in 1960.

GMU Econ alum Dominic Pino shares this happy news: “Nissan employees in New Jersey decertify UAW.” A slice:

You wouldn’t know it from the wall-to-wall positive media coverage, but the Nissan workers are actually more representative of national trends than the VW workers are. UAW membership declined last year to 370,000. It was nearly 400,000 in 2020, and it peaked at 1.5 million in 1970. The UAW has far more retired members than active members, and roughly the same number work for the University of California system as work for General Motors. The overall union membership rate in the U.S. last year was a record-low 10 percent, and it was only 6 percent in the private sector.

Man had entered the Nineteenth Century using only his own and animal power, supplemented by that of wind and water, much as he had entered the Thirteenth, or, for that matter, the First. He entered the Twentieth with his capacities in transportation, communication, production, manufacture and weaponry multiplied a thousandfold by the energy of machines.

Man had entered the Nineteenth Century using only his own and animal power, supplemented by that of wind and water, much as he had entered the Thirteenth, or, for that matter, the First. He entered the Twentieth with his capacities in transportation, communication, production, manufacture and weaponry multiplied a thousandfold by the energy of machines. The mischief begins when, instead of calling forth the activity and powers of individuals and bodies, it [the government] substitutes its own activity for theirs; when, instead of informing, advising, and, upon occasion, denouncing, it makes them work in fetters, or bids them stand aside and does their work instead of them.

The mischief begins when, instead of calling forth the activity and powers of individuals and bodies, it [the government] substitutes its own activity for theirs; when, instead of informing, advising, and, upon occasion, denouncing, it makes them work in fetters, or bids them stand aside and does their work instead of them. Development requires helping the poor find their way from farm to factory, and from factory to office, classroom, and laboratory. This requires massive investment, which in turn requires sophisticated financial intermediation. It is for this reason that the trade and financial dimensions of globalization are complementary.

Development requires helping the poor find their way from farm to factory, and from factory to office, classroom, and laboratory. This requires massive investment, which in turn requires sophisticated financial intermediation. It is for this reason that the trade and financial dimensions of globalization are complementary. Most often, and especially when dealing with strangers, money prices take an item out of the political or ethical realm in a way that paradoxically purifies it. Allocating goods by social class or race or violence or political pressures or party membership is disgraceful. A price for most goods is merely a price. No shame attached.

Most often, and especially when dealing with strangers, money prices take an item out of the political or ethical realm in a way that paradoxically purifies it. Allocating goods by social class or race or violence or political pressures or party membership is disgraceful. A price for most goods is merely a price. No shame attached.